Why You Are Either the Solution – or the Problem: The Omission Bias

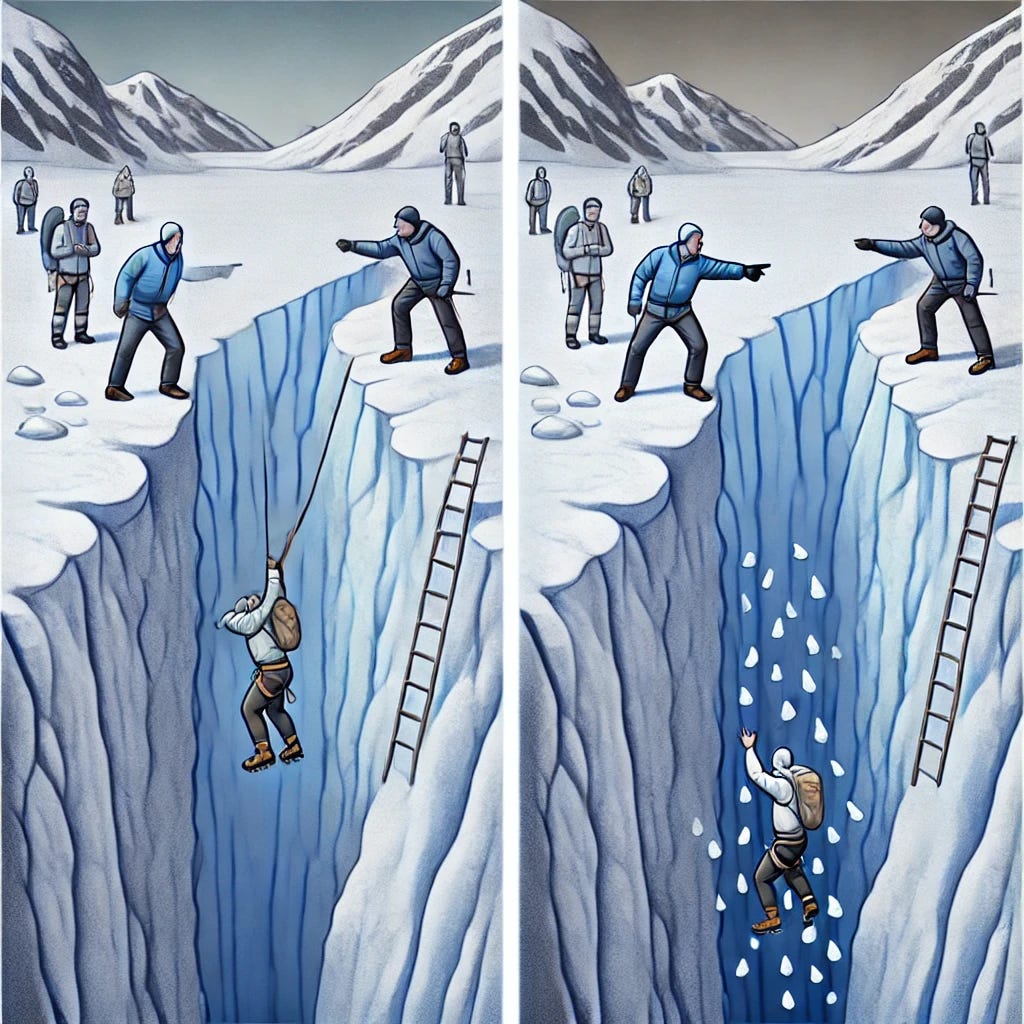

Imagine you’re on a glacier with two climbers. The first slips and falls into a crevasse. You have the chance to call for help, but you don’t, and the climber dies. The second climber you actively push into the ravine, and he perishes as well. Which weighs more heavily on your conscience?

Logically, both situations are equally terrible—they both result in death. But most people feel the passive scenario, where you did nothing, is less morally wrong than actively pushing someone to their death. This is the omission bias, a psychological tendency that makes us view inaction as less harmful than action, even when the outcomes are identical.

The Omission Bias in Real-World Scenarios

Now, let’s say you’re the head of the Federal Drug Administration, faced with a decision on approving a drug for terminally ill patients. The drug can save 80% of patients, but it has fatal side effects that kill 20% instantly. What would you do?

Most people would refuse to approve the drug, fearing the 20% death rate more than the potential to save the other 80%. This is a classic example of the omission bias. Approving the drug feels like a more severe act than withholding it, even though doing nothing would result in more deaths overall.

Even if you are aware of this bias and choose to approve the drug, you would face backlash if the first patient dies. A media frenzy might ensue, potentially costing you your job. Politicians and civil servants are well aware of this bias, and many exploit it—knowing that inaction, while harmful, is easier to justify than action with visible consequences.

How Omission Bias Shapes Society

The omission bias deeply affects laws and social norms. For example, active euthanasia, even when it aligns with a patient's wishes, is often illegal, while withholding life-saving measures is allowed under laws like "Do Not Resuscitate" (DNR) orders. Society, it seems, is more comfortable with inaction leading to death than with action that results in the same outcome.

This bias also explains why some parents refuse to vaccinate their children, despite the clear benefits. Vaccination reduces the risk of catching a disease and also prevents the spread of illness to others. However, because there is a tiny risk of adverse reactions, some parents choose to do nothing, even though inaction leaves their children and society vulnerable. If those children later contract a preventable disease, the parents’ inaction has caused harm. But that’s the key: inaction feels less severe than taking an action, like administering the vaccine, even though the risks of inaction may be greater.

Omission Bias in Business and Investing

The omission bias extends into the business world as well. Investors are more forgiving of companies that do nothing and fail to innovate than they are of companies that take risks and fail with new products. Yet both paths lead to failure. Sitting on bad stocks feels less wrong than actively buying more poor-performing shares. Failing to add an emissions filter to a coal plant seems better than removing one for cost savings, even though both scenarios result in harm to the environment.

In business, this bias means people are often judged less harshly for what they don’t do than for what they do, even if the outcomes are equally damaging.

Action Bias vs. Omission Bias

The action bias, which we discussed previously, compels us to act in uncertain situations, even when waiting might be better. In contrast, the omission bias makes us hesitate to act, even when inaction leads to a worse outcome. The action bias tends to arise in confusing or uncertain situations, where people compensate for the lack of clarity with hyperactivity. The omission bias, on the other hand, shows up when the situation is clearer, but inaction feels like the safer, less culpable option.

Conclusion: Be Aware of the Omission Bias

The omission bias is subtle but powerful. It often goes unnoticed because inaction is less visible than action. But as the famous slogan from the 1960s student movements says, “If you’re not part of the solution, you are part of the problem.” Whether through action or inaction, you’re still responsible for the outcome. Understanding the omission bias can help you make more balanced decisions, where doing nothing is no longer seen as the safer, more moral choice by default.